It’s good to be updating this website after a long silence with the news that in April, a new Philip Kerr novel, Metropolis, will be published. Set in the Weimar years, it takes Bernie right back to his beginnings as a murder squad detective, amid the sordid and chaotic Berlin underground. Infused as ever with his pitch-black humour, it’s an excellent novel, made all the more of an achievement by the fact that it was conceived and produced under the most daunting circumstances imaginable.

In July 2017, in the inappropriately sunny office of a London cancer clinic, Phil learned that he had stage 4 metastatic cancer and it was incurable. With characteristic courage he asked the doctor how long he had. Between one and two years, she suggested. Plainly keen to impart more optimistic news, she volunteered that she had once, in a long career, known a single patient at the same stage live for five years.

When we got into the car, Phil exhaled. ‘So I’ve got five years.’ In the event, he had eight months.

That defiance, which also enabled him to write the whole of Metropolis against this desperately dark background, is precisely the same characteristic that drives his fictional alter ego, Bernie Gunther. As Bernie dodges and weaves among the grim monsters of Nazi Germany, he always retains a sense of his own invincibility.

Mocking, hard-bitten, cynical and sentimental, there’s no doubt that Bernie Gunther is a very close representation of Philip himself. Having grown up in the 1960s, with the goodies and baddies version of World War Two in the cinema and on TV, Philip wanted to create a protagonist who would embody the true moral ambiguities of the period. He loved to paint Bernie into an ethical corner ‘so he can’t cross the floor without getting paint on his shoes.’

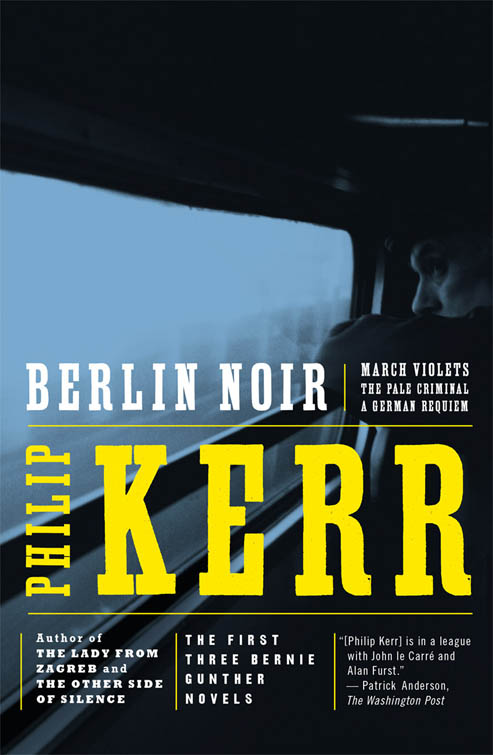

Philip’s was a remarkable talent and it was fascinating to see it operating close up over the space of thirty years. Before we met he had written a couple of unpublished novels while he searched for his theme, before working out the perfect combination of what he loved – detective fiction and twentieth century Germany. In particular, he was tickled by the idea of a detective solving everyday crimes against the backdrop of the greatest crime of the century. As Bernie says in The Lady From Zagreb, ‘Being a Berlin cop in 1942 was a little like putting down mousetraps in a cage full of tigers.’

The first three Bernie novels were a success, but he never wanted to be a one-note author and at the end of A German Requiem he actively suggested killing Gunther off, before being reluctantly persuaded to reprieve him. Even so, it was fifteen years before he returned to Bernie and in that time he explored a huge variety of genres from sci-fi, sport and hi-tech thrillers, to his children’s series, The Children of the Lamp. Film was his other great love and his knowledge was encyclopaedic. He spent an inordinate amount of time on screenplays, leading to many gratifying brushes with Hollywood. Phil’s love of business and deal-making – unusual in such an otherworldly industry as writing – were perfect for pitching movies. Once, having been flown to the US by Tom Cruise, who had bought the rights to one of his novels, Phil took the opportunity to set up an evening meeting with Robert de Niro, without mentioning it to Tom. That chutzpah rebounded on him when Cruise was delayed and he found himself sweating in the film star’s trailer, facing the awful prospect of standing up Robert de Niro. Despite this tricky situation, his contacts with Hollywood continued unabated, and currently Tom Hanks is developing the Bernie Gunther series for TV.

The world is full of writer’s rules and Philip was partial to his own. Imbued with a strict Scottish Protestant work ethic, he believed in keeping ‘office hours’ of 8am to 5pm. But as life went on, these limits went by the board. He wrote every day, including Saturday and Sunday. Every holiday. He wrote on Christmas day. He wrote in the chemotherapy suite.

His output was prodigious. He loved to quote Iris Murdoch, when she was asked how long she left between novels. ‘Oh, a long time. About forty minutes.’ The only thing to match his ferocious industry was his extraordinary self-belief. Whenever the (very) occasional bad review irked him, he tended to repeat David Hockney’s motto. ‘It’s not what the critic thinks, it’s what I think that matters.’

You could not wish for a better writer to live with – his pep talks were generous and inspirational, and he seemed to believe that anyone could achieve if only they applied themselves. His approach to failure – a certain part of every writer’s life – was also valuable. If a novel wasn’t working, he moved on immediately and always advised me to do the same.

I have never met any writer with more ideas. He loved mining the events of twentieth-century Europe and was always on the lookout for a country or situation in which Bernie might intervene. Perhaps our happiest times were research trips; whether to the Berghof, or Heydrich’s country home in Prague, or Potsdam. Once, the whole family was booked into the Hotel Lutetia in Paris, on the grounds that it had been the headquarters of the Abwehr, the German counter-intelligence service.

Counter-intuitively, Philip did not want his last novel to feature an ageing Bernie, and thus Metropolis takes his hero back to 1928 when he was a young cop, just starting out. Most readers like their Bernie world-weary – the jaded, philosophical Gunther who says, ‘I’m no longer young enough, nor quite thin enough, to share a single bed with anything other than a hangover or a cigarette’. They might wonder if a fresh-faced younger model can measure up.

They needn’t worry. As Metropolis triumphantly reveals, cynicism, mockery, intelligence and wit were always Bernie’s birthright.